Digest of Resources for Pre-Service Music Teachers

Acknowledgments: Special thanks for the contributions of Blair Chadwick and Johnathan Vest, who gave me permission to share information verbatim from their PowerPoint presentation, and to John Seybert (formerly of Seton Hill University), Ann C. Clements, Robert Gardner, Steven Hankle, Darrin Thornton, Linda Thornton, and Sarah Watt (Penn State University), Dr. Rachel Whitcomb (Duquesne University), and Robert Dell (Carnegie-Mellon University).

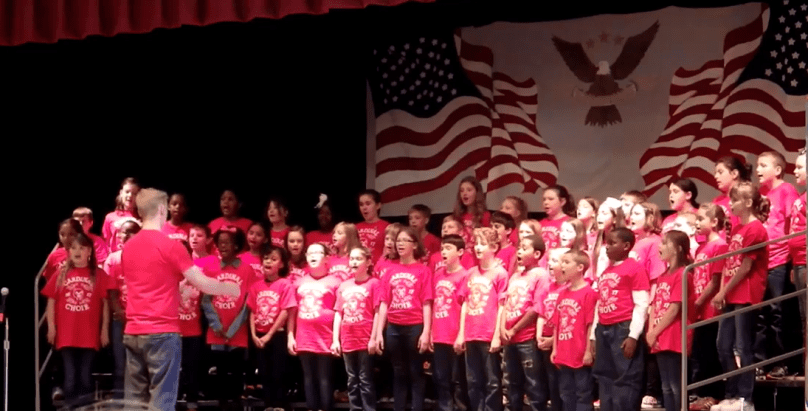

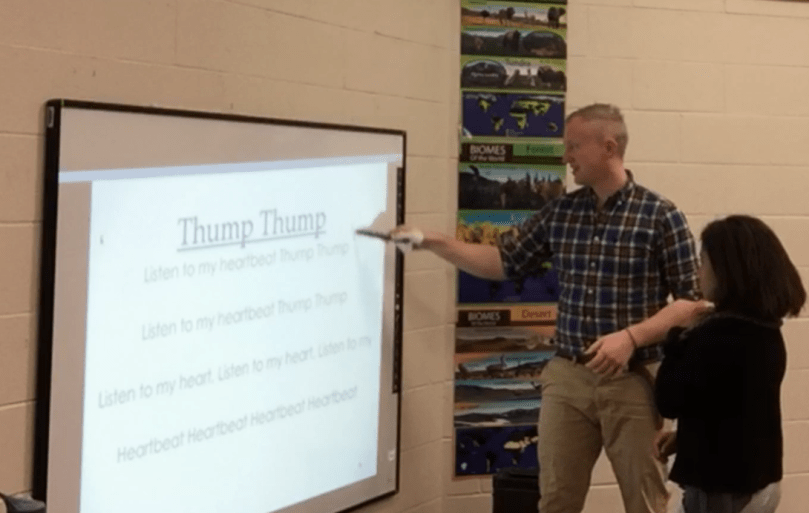

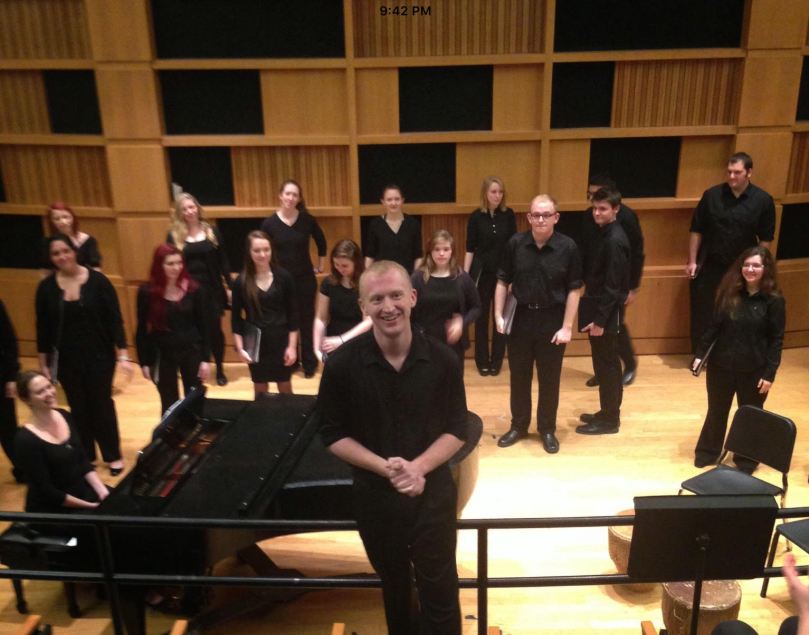

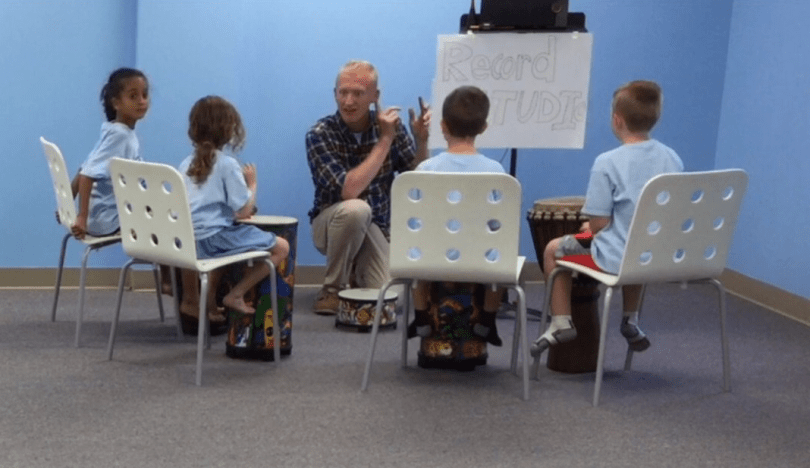

Photo credits: David Dockan, my former student, graduate of West Virginia University, now Choir Director / Music Teacher at JEJ Moore Middle School in Prince George, VA.

If you are not fortunate enough to own a copy of A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music by Ann. C. Clements and Rita Klinger (which I heartily recommend you go out and buy, beg, borrow, or steal), this blog provides a practical overview of field experiences in music education, recommendations for the preparation of all music education majors, and a bibliographic summary of additional resources. Representing that most critical application of in-depth collegiate study of music education methods, conducting, score preparation, ear-training, and personal musicianship and understanding of pedagogy on voice, piano, guitar, and band and string instruments, the student teaching experience provides the culminating everyday “nuts and bolts” of effective music education practice in PreK-12 classrooms.

If you are not fortunate enough to own a copy of A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music by Ann. C. Clements and Rita Klinger (which I heartily recommend you go out and buy, beg, borrow, or steal), this blog provides a practical overview of field experiences in music education, recommendations for the preparation of all music education majors, and a bibliographic summary of additional resources. Representing that most critical application of in-depth collegiate study of music education methods, conducting, score preparation, ear-training, and personal musicianship and understanding of pedagogy on voice, piano, guitar, and band and string instruments, the student teaching experience provides the culminating everyday “nuts and bolts” of effective music education practice in PreK-12 classrooms.

Possibly the best definition of “a master music teacher” and the process for “hands-on” field training comes from the Penn State University handbook, Partnership for Music Teacher Excellence: A Guide for Cooperating Teachers, Student Teachers, and University Supervisors.

“The goal of the Penn State Music Teacher Education Program is to prepare exemplary music teachers for K-12 music programs. Such individuals can provide outstanding personal and musical models for children and youth and have a firm foundation in pedagogy on which to build music teaching skills. Penn State B.M.E. graduates exhibit excellence in music teaching as defined below.”

“As PERSONAL MODELS for children and youth, music teachers are caring, sensitive individuals who are willing and able to empathize with widely diverse student populations. They exhibit a high sense of personal integrity and demonstrate a concern for improving the quality of life in their immediate as well as global environments. They establish and maintain positive relations with people both like and unlike themselves and demonstrate the ability to provide positive and constructive leadership. They are in good mental, physi

cal, and social health. They demonstrate the ability to establish and achieve personal goals. They have a positive outlook on life.”

“As MUSICAL MODELS, they provide musical leadership in a manner that enables others to experience music from a wide variety of cultures and genres with ever-‐‑increasing depth and sensitivity. They demonstrate technical accuracy, fluency, and musical understanding in their roles as performers, conductors, composers, arrangers, improvisers, and analyzers of music.”

“As emerging PEDAGOGUES, they are aware of patterns of human development, especially those of children and youth, and are knowledgeable about basic principles of music learning and learning theory. They are able to develop music curricula, select appropriate repertoire, plan instruction, and assess music learning of students that fosters appropriate interaction between learners and music that results in efficient learning.” — Penn State University School of Music

Making a smooth transition from “music student” to “music teacher” requires a focus on four goals:

- Preparation to your placement in music education field assignments

- Understanding of the relationships between your cooperating teacher(s) and the university supervisor (and you!) and promotion of positive communications

- Adjusting to new environments

- Development of professional responsibilities

As mentioned before, details of these should be reviewed in a reading of the introduction to A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music by Ann. C. Clements and Rita Klinger.

Not to “toot my own horn,” but you are invited to peruse my past blogs on this subject:

- Transitioning from Collegiate to Professional – Part I

- Transitioning from Collegiate to Professional – Part II

- Transitioning from Collegiate to Professional – Part III

Observations

“Take baby steps,” they say? Before your college music education professors release you to direct a middle school band, teach a general music class, or rehearse the high school choir, you will be asked to observe as many music programs as possible.

My advice to all pre-service teachers is, regardless of your formal assignments by your music education coordinator, try to find time to observe a multitude of different locations, levels, and socioeconomic examples of music classes. Do not limit yourself to those types of jobs you “think” you eventually will seek or be employed:

- Urban, rural, and suburb settings in poor, middle, and upper-middle socioeconomic areas

- Large and small school populations

- Both private and public school entities

- Elementary, middle, and high school grades

- General music, tech/keyboard, guitar, jazz, band, choral, and string classes

- Assignments as different from your own experiences in music-making

Ann Clement and Rita Klinger make the distinction between simply observing and analyzing what you see:

“Observation is a scientific term that means to be or become aware of a phenomenon through careful and directed attention. To observe is to watch attentively with specific goals in mind. Inference is the act of deriving logical conclusions from premises known or assumed to be true. Inference is the act of reason upon an observation. A good observation will begin with pure observation devoid of inference. After an observation of the phenomenon being studied has been completed, it is appropriate to infer meaning to what has been observed. Adding inference after an observation completes the observation cycle — making it a meaningful observation.” — A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music

Some tips (from Student Teaching in Music: Tips for a Successful Experience by Blair Chadwick and Dr. Johnathan Vest):

- Have a specific goal for the observation in mind before you begin

- Make copious notes, but don’t write down everything.

- Write down techniques, quotes, musical directions or teacher behaviors that seem important.

- Don’t be overly critical of your master or cooperating teacher during the observation process. Remember, they are the expert, you are the novice. Your perspective changes when you are in front of the class.

- Hand-write your notes. An electronic device, although convenient, is louder and can provide distraction for the teacher and students, and you. Write neatly so you can transcribe the notes later.

- An small audio recorder can be very useful in case you want to go back and hear something again.

It is appropriate to mention something here about archiving your notes and professional contacts. It is essential that you organize and compile all of the data as you go along… catalog the information in your “C” files (don’t just stuff papers in a drawer somewhere):

- Contacts (cooperating/master teachers and administrators’ phone/email addresses)

- Course work outlines and class observation journals

- Concerts (your own solo and ensemble literature and school repertoire)

- Conferences (session handouts, programs)

Why is this important? Don’t be surprised if/when you are asked to teach in a specialty or grade level outside your “major emphasis,” and you want to find that perfect teaching technique or musical selection previously observed that would be a help in your lesson.

Student Teaching

The success of the student teaching experience depends on all its parts working together. They include:

- The Student Teacher

- The Cooperating Teacher

- The University Supervisor

- The Students

- The Administration and other teachers and personnel in the building

First, check out your university’s guidelines (of course), but here are “The Basics.”

- Punctuality (Early = on time; On time = late; Late = FIRED)

- Dress and Appearance: Be comfortable yet professional. Be aware of a dress code if one exists, as well as restrictions on tattoos, piercings, and long hair length (gentlemen.)

- Parking/Checking-In: Know this information BEFORE your first day

- Materials and Paperwork: Contact your Cooperating Teacher BEFORE the first day. Know what you need and bring it with you on the first day.

Teacher Hub in “A Student Teaching Survival Guide” spelled out a few more recommendations:

Dress for success (professionally)

Dress for success (professionally)- Always be prepared (checklists, planner, to-do’s)

- Be confident and have a positive attitude (if needed, “fake” self-confidence)

- Participate in all school activities (everything you can fit into your schedule: staff meetings, extra-curricular activities assigned to the cooperating teacher, and even chaperone duties for a school dance, etc.)

- Stay clear of drama (no gossip!)

- Don’t take it personally (embracing constructive feedback and criticism)

- Ask for help (that’s why you and mentor teachers are there)

- Edit your social media accounts (privacy settings and no school student contacts)

- Approach student teaching as a long interview (always, throughout the student teaching assignment: “best foot forward” and showcase of all of your qualities)

- Stay healthy (handling stress, good sleep, and other positive health habits)

Common questions that may be asked by the student teacher (Chadwick and Vest):

- Will my cooperating teacher (CT) and school be a good fit for me?

- Will I “crash and burn” my first time in front of the class?

- What if my CT won’t let me teach?

- What if my CT “throws me to the wolves” on the first day?

- Will the students respect me?

- How will I be graded?

- Will I pass the Praxis??

Planning

Chapter 2 “Curriculum and Lesson Planning” in A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music provides 12 pages covering scenarios, discussions, and worksheets on all aspects of instructional planning, including the topics of philosophy of music teaching, teaching with and without a plan, long-term planning, and assessment and grading.

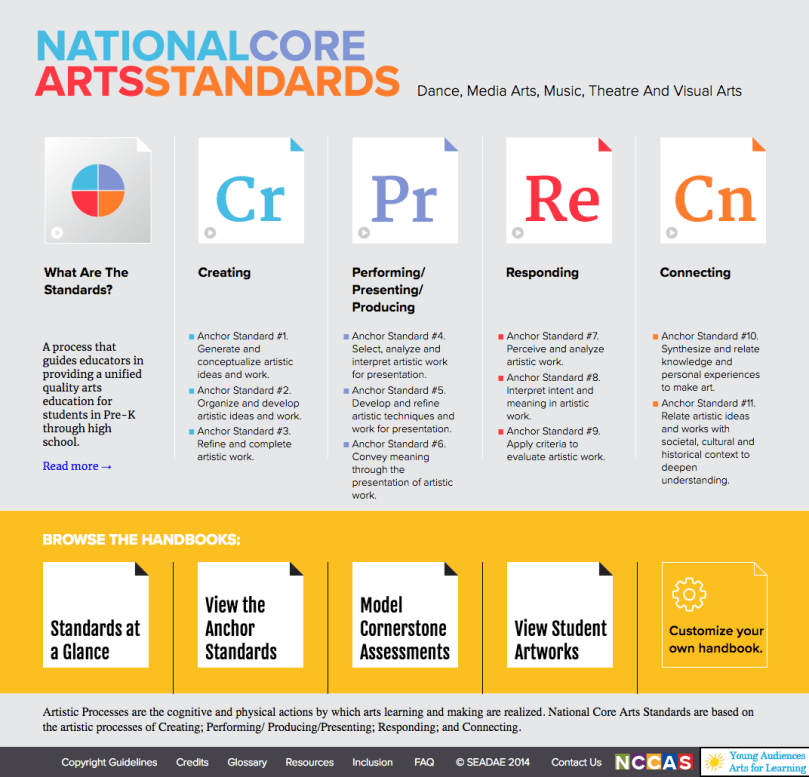

If you are unfamiliar with the terms “formative,” “summative,” “diagnostic” and “authentic” assessment, or other educational jargon, or are not fully aware of your state’s arts and humanities standards and the National Core Arts Standards, don’t panic. (Many of us “veteran” music teachers were in the same boat at the beginning of student teaching, regardless of how much material was introduced in our education methods courses.) Do some “catch-up” by visiting the corresponding websites. For example, in  Pennsylvania, you should be a member of PCMEA and take advantage of the research of the PMEA Interactive Model Curriculum Framework. Some educational “buzz words” and acronyms were explored in a previous blog here. It should be noted that, although you won’t be expected to know the full PreK-12 music curriculum while student teaching, when you are hired as “the music specialist,” you would likely be the professional who will be assigned to write and update that same curriculum… so get to know it ASAP. (On my second day in my first job, my JSHS principal came to me and said a course of study for 8th grade music appreciation was due on his desk by the last week of the semester! No, like you, I was not trained in writing curriculum in college!)

Pennsylvania, you should be a member of PCMEA and take advantage of the research of the PMEA Interactive Model Curriculum Framework. Some educational “buzz words” and acronyms were explored in a previous blog here. It should be noted that, although you won’t be expected to know the full PreK-12 music curriculum while student teaching, when you are hired as “the music specialist,” you would likely be the professional who will be assigned to write and update that same curriculum… so get to know it ASAP. (On my second day in my first job, my JSHS principal came to me and said a course of study for 8th grade music appreciation was due on his desk by the last week of the semester! No, like you, I was not trained in writing curriculum in college!)

From the Penn State University Partnership for Music Teacher Excellence: A Guide for Cooperating Teachers, Student Teachers, and University Supervisors, the following criteria are recommended to be used by the cooperating teacher and the student teacher to assess the effectiveness of a long-term course of study. (Sample plans are provided here.)

- Stated learning principles are related to specific learner or student teacher

activities. - The importance of the course of study is explained in terms learners would likely

accept and understand. - Each goal is supported by specific objectives.

- The sequence of the objectives is appropriate.

- The goals and objectives are realistic for this group of learners.

- The objectives consider individual differences among learners.

- The content presentation indicates complete and sequential conceptual

understanding. - The presentation is detailed enough that any teacher in the same field could

teach this unit. - The amount of content is appropriate for the length of time available.

- A variety of teaching strategies are included in the daily activities.

- The teaching strategies indicate awareness of individual differences.

- The daily plans include a variety of materials and resources.

- The objectives, teaching strategies, and evaluations are consistent.

- A variety of evaluative techniques is employed.

- Provisions are made for communicating evaluative criteria to learners.

- The materials are neatly presented.

It is important sit side-by-side with your cooperating teacher and discuss some of these “essential questions” of instructional planning and assessment of student teaching:

- What is the purpose of the learning situation?

- What provision have you made for individual differences in learner needs, interests, and abilities?

- Are your plans flexible and yet focused on the subject?

- Have you provided alternative plans in case your initial planning was not adequate for the period (e.g. too short, too long, too easy, too hard)?

- Can you maintain your poise and sense of direction even if your plans do not go as you anticipated?

- Can you determine where in your plans you have succeeded or failed?

- On the basis of yesterday’s experiences, what should be covered today?

- Have you provided for the introduction of new material and the review of old material?

- Have you provided for the development of musical understanding and attitude as well as performance skills?

Getting Your Feet Wet… Becoming an “Educator”

[Source: Chadwick and Vest]

Be attentive to the needs of the students and your cooperating teacher. If you see a need that arises that the CT cannot or is not addressing, then take action. Don’t always wait to be told what to do. These situations may include:

- Singing or playing with students who are struggling

- Work with a section or small group of students

- Helping a student with seat/written work

- Attending to a a non-musical problem (such as student behavior)

Your supervising teacher or music education coordinator will probably instruct you on how much and when to teach, but each school and CT is different. In general, you should start teaching a class full-time by week 3 and have at least two weeks of full-load teaching per placement. (This is not always possible.)

Remember that any experience is good experience, so be grateful if you are asked to teach early-on in your experience.

What the supervising and/or cooperating teachers are looking for during an observation:

- The Lesson Plan

- Lesson organization (components, logical flow, pacing, time efficiency)

- Required components included

- National and State Standards Included—and these have/are changing!!!!

- Objectives stated in observable terms and tied directly to your assessment(s)

- What the US/CT is looking for during an observation

- Teaching Methods

- Questioning techniques (stimulate thought, higher order, open-ended, wait time)

- Appropriate terminology use

- Student activities that are instructionally effective

- Teacher monitoring of student activities, assisting, giving feedback

- Opportunities for higher order thinking

- Teacher energy/enthusiasm

- Classroom Management

- Media and materials are appropriate, interesting, organized and related to the unit of study.

- Teacher “with-it-ness”

- Student behavior management (consistency, classroom procedures in place, students understand expectations)

- Student Involvement/Interest/Participation in the Lesson

- Student verbal participation

- Balance of teacher talk/student talk

- Lots of “musicing” (singing, playing, listening, moving)

- Student motivation

- Student understanding of what to do and how to do it

- Classroom Atmosphere

- Positive, “can-do” atmosphere

- Student questions, teacher response

- Helpful feedback

- Verbal and non-verbal evidence that all students are accepted and feel that they belong

Student teaching is the opportunity of a lifetime. This is when you get to practice your pedagogical skills, make invaluable professional connections, and learn lifelong lessons. Sure, it will take a lot of hard work and dedication. As TeacherHub concluded, “Use this time to learn and grow and make a great impression. Stay positive and remember student teaching isn’t forever – if you play your cards right, you will have a classroom of your own very soon.”

PKF

Bibliography

A Field Guide to Student Teaching in Music, Ann C. Clements and Rita Klinger

A Guide to Student Teaching in Band, Dennis Fisher, Lissa Fleming May, and Erik Johnson, GIA 2019

Handbook for the Beginning Music Teacher, Colleen Conway and Tom Hodgman, 2006

Including Everyone: Creating Music Classrooms Where All Children Learn, Judith A. Jellison, 2015

Intelligent Music Teaching, Robert Duke

Music in Special Education, Mary S. Adamek and Alice Ann Darrow, 2010

Partnership for Music Teacher Excellence: A Guide for Cooperating Teachers,

Student Teachers, and University Supervisors, Penn State University Music Education Faculty Ann Clements, Robert Gardner, Steven Hankle, Darrin Thornton, Linda Thornton, Sarah Watts https://music.psu.edu/sites/music.psu.edu/files/music_education/pmte-student_teaching_handbook.pdf

Remixing the Classroom: Toward an Open Philosophy of Music Education, Randall Everett Allsup, 2016

A Student Teaching Survival Guide, Janelle Cox https://www.teachhub.com/student-teaching-survival-guide

Student Teaching in Music: Tips for a Successful Experience, Blair Chadwick and Dr. Johnathan Vest https://www.utm.edu/departments/musiced/_docs/NAfME%20%20Student%20Teaching%20in%20Music.pptx

Teaching Music in the Urban Classroom, Carol Frierson-Campbell, ed.

Teaching with Vitality: Pathways to Health and Wellness for Teachers and Schools, Peggy D. Bennett, 2017

© 2019 Paul K. Fox

that seem to be the most prevalent:

that seem to be the most prevalent:

The “new” definition of retirement includes a unique collection of synonyms. Gone are the designations “seclusion,” “privacy,” “withdrawal,” “retreating” and “disappearing” based on archaic models of retiring when the average life expectancy at birth in the 1800s was 38 and in the 1900s was 47. (Merriam-Webster and others still show these words on their online dictionaries!) Now, some of the more creative descriptors for retirement are “renewment,” “rewirement,” “rest-of-life,” “second beginnings,” and “reinvention.”

The “new” definition of retirement includes a unique collection of synonyms. Gone are the designations “seclusion,” “privacy,” “withdrawal,” “retreating” and “disappearing” based on archaic models of retiring when the average life expectancy at birth in the 1800s was 38 and in the 1900s was 47. (Merriam-Webster and others still show these words on their online dictionaries!) Now, some of the more creative descriptors for retirement are “renewment,” “rewirement,” “rest-of-life,” “second beginnings,” and “reinvention.”

Feeling you were “kicked to the curb,” “downsized,” “minimized,” or somehow “forced” to resign or retire comes from many scenarios:

Feeling you were “kicked to the curb,” “downsized,” “minimized,” or somehow “forced” to resign or retire comes from many scenarios:

In retirement, this can be frustrating. You can’t tell somebody else how to run their operation. Some people do not want to hear criticism, nor do they care what your opinion is, nor do they want to change their traditions or fine-tuned (?) step-by-step procedures. You on the other hand want things to improve, e.g. better training, more consistent application of the rules, etc., and therefore you feel “unrequited stress.”

In retirement, this can be frustrating. You can’t tell somebody else how to run their operation. Some people do not want to hear criticism, nor do they care what your opinion is, nor do they want to change their traditions or fine-tuned (?) step-by-step procedures. You on the other hand want things to improve, e.g. better training, more consistent application of the rules, etc., and therefore you feel “unrequited stress.”

However, invest your time wisely. Retirees deserve a life of their own and opportunities for unstructured “time-off.” Don’t forget the other items on your “bucket lists” (like travel, “encore career,” and volunteering). Serving as your family’s childcare “safety net” is nice, but don’t let this schedule dominate everything you do in your retirement… trading one job for another… with no financial compensation (but a whole lot of fun, I know).

However, invest your time wisely. Retirees deserve a life of their own and opportunities for unstructured “time-off.” Don’t forget the other items on your “bucket lists” (like travel, “encore career,” and volunteering). Serving as your family’s childcare “safety net” is nice, but don’t let this schedule dominate everything you do in your retirement… trading one job for another… with no financial compensation (but a whole lot of fun, I know). Again, that focus on “first things first” (remember the book of the same name by Stephen Covey?) and “take care of yourself, too!”

Again, that focus on “first things first” (remember the book of the same name by Stephen Covey?) and “take care of yourself, too!”

That means, according to TIPS Retirement for Music Educators by Verne A. Wilson (MENC 1989), at least three years before you leave your full-time employment:

That means, according to TIPS Retirement for Music Educators by Verne A. Wilson (MENC 1989), at least three years before you leave your full-time employment: Robert Delamontagne writes in detail about using the

Robert Delamontagne writes in detail about using the  Delamontagne labels the characteristics of each E-Type. After reading his book, which ones are closest to resembling you and your spouse?

Delamontagne labels the characteristics of each E-Type. After reading his book, which ones are closest to resembling you and your spouse? On their book jacket, Duckworth and Langworthy promote their work as “a call to action on your own behalf” to:

On their book jacket, Duckworth and Langworthy promote their work as “a call to action on your own behalf” to: Life Themes Profiler, a comprehensive assessment tool developed by David Borchard and laid out initially in Chapter 4, will help you understand and graph the retirement themes and “your intentions for the next chapter of your life.”

Life Themes Profiler, a comprehensive assessment tool developed by David Borchard and laid out initially in Chapter 4, will help you understand and graph the retirement themes and “your intentions for the next chapter of your life.” Obviously, fulfilling your “bucket lists” and goals will influence the structure of your daily/weekly schedule. According to Ernie Zelinski, with or without “a job,” you need to find a “work-life balance” and devote equal time to these essential priorities:

Obviously, fulfilling your “bucket lists” and goals will influence the structure of your daily/weekly schedule. According to Ernie Zelinski, with or without “a job,” you need to find a “work-life balance” and devote equal time to these essential priorities: Dave Hughes echoes these sentiments with his “four essential ingredients for a balanced life” in the book Design Your Dream Retirement: How to Envision, Plan for, and Enjoy the Best Retirement Possible (2015):

Dave Hughes echoes these sentiments with his “four essential ingredients for a balanced life” in the book Design Your Dream Retirement: How to Envision, Plan for, and Enjoy the Best Retirement Possible (2015): Do something every day that will expand your mind, stimulate your intellect, or increase your curiosity quotient.

Do something every day that will expand your mind, stimulate your intellect, or increase your curiosity quotient. Although the exact number of boomers and seniors who experience sleep problems is hard to pinpoint, a national study of our aging population suggests nearly 42 percent of those surveyed have sleep difficulties. That figure is beyond an epidemic.

Although the exact number of boomers and seniors who experience sleep problems is hard to pinpoint, a national study of our aging population suggests nearly 42 percent of those surveyed have sleep difficulties. That figure is beyond an epidemic. Regular physical activity is a must. Quoting from a future article I plan to submit to the state journal of Pennsylvania Music Educators Association PMEA News: “The definition of ‘exercise,’ especially in order to receive cardiovascular benefits, is to raise your heart rate for 30 minutes or more. Leaving your La-Z-Boy to let the dogs out or looking for the remote does not count!”

Regular physical activity is a must. Quoting from a future article I plan to submit to the state journal of Pennsylvania Music Educators Association PMEA News: “The definition of ‘exercise,’ especially in order to receive cardiovascular benefits, is to raise your heart rate for 30 minutes or more. Leaving your La-Z-Boy to let the dogs out or looking for the remote does not count!” This final category of “pre-retirement planning” has everything to do with living with independence and security as we grow older. Many Baby Boomers just starting their retirement journey may not actually see this as “a big deal” right now. However, developing a long term “backup plan” for maintaining our health care, mobility, and comfortable living is critical. Again… we must think ahead!

This final category of “pre-retirement planning” has everything to do with living with independence and security as we grow older. Many Baby Boomers just starting their retirement journey may not actually see this as “a big deal” right now. However, developing a long term “backup plan” for maintaining our health care, mobility, and comfortable living is critical. Again… we must think ahead! Fifty-five percent of our respondents wanted to stay in their own homes, with help as needed, as they got older and required more care. But a recent AARP survey revealed that only about half of older adults thought their homes could accommodate them “very well” as they age; twelve percent said “not well” or “not well at all.”

Fifty-five percent of our respondents wanted to stay in their own homes, with help as needed, as they got older and required more care. But a recent AARP survey revealed that only about half of older adults thought their homes could accommodate them “very well” as they age; twelve percent said “not well” or “not well at all.”

Denial

Denial

I submit there are basically three ways to learn something new by reading about it. One is the tutorial format, a.k.a. an instrument of “programmed learning.” Another approach is the comprehensive reference manual or user guide. Finally, many people prefer a narrative story, perhaps a fictitious account that features characters exploring and revealing insights on the topic you are studying.

I submit there are basically three ways to learn something new by reading about it. One is the tutorial format, a.k.a. an instrument of “programmed learning.” Another approach is the comprehensive reference manual or user guide. Finally, many people prefer a narrative story, perhaps a fictitious account that features characters exploring and revealing insights on the topic you are studying. If you were looking for the reference manual, I recommend Ernie Zelinski’s How to Retire Happy, Wild, and Free (2016). The chapters are laid out by general concepts you need to understand. However, as in many user guides, you could turn to almost any page in the volume, jump around (in any order) to specific areas on which to focus, e.g. tips on travel (page 165) to health/wellness (page 109), and not lose the overall meaning.

If you were looking for the reference manual, I recommend Ernie Zelinski’s How to Retire Happy, Wild, and Free (2016). The chapters are laid out by general concepts you need to understand. However, as in many user guides, you could turn to almost any page in the volume, jump around (in any order) to specific areas on which to focus, e.g. tips on travel (page 165) to health/wellness (page 109), and not lose the overall meaning.

The contents of It’s Never Too Late to Begin Again are divided into a weekly course of study:

The contents of It’s Never Too Late to Begin Again are divided into a weekly course of study: The fictitious “Larry and Janice Sparks” share anecdotes of their experiences, modeling potential opportunities of retirees enhancing their relationships, stimulating their minds, revitalizing their bodies, growing spiritually… basically rekindling passion in every area of their lives.

The fictitious “Larry and Janice Sparks” share anecdotes of their experiences, modeling potential opportunities of retirees enhancing their relationships, stimulating their minds, revitalizing their bodies, growing spiritually… basically rekindling passion in every area of their lives. You will notice that all three texts cover many of the same subjects, but are vastly different in methodology, style/design, and overall structure.

You will notice that all three texts cover many of the same subjects, but are vastly different in methodology, style/design, and overall structure. at the Seven Springs Mountain Resort in Pennsylvania on July 11-13, 2016.

at the Seven Springs Mountain Resort in Pennsylvania on July 11-13, 2016.

Take up a new hobby. Now that you have the time, go exploring… and the skies the limit! But don’t forget, anything worth doing “engages the mind!”

Take up a new hobby. Now that you have the time, go exploring… and the skies the limit! But don’t forget, anything worth doing “engages the mind!”

If you have not read a previous blog of mine, “Advice from Music Teacher Retirees to Soon-To-Be Retirees,” check out the reprinted version on the Edutopia website:

If you have not read a previous blog of mine, “Advice from Music Teacher Retirees to Soon-To-Be Retirees,” check out the reprinted version on the Edutopia website:  Just like a rehearsal – start off with a mind warm-up! Go to the website

Just like a rehearsal – start off with a mind warm-up! Go to the website  Leo the Tech Guy program and site at

Leo the Tech Guy program and site at  Finally, hobbyist websites are a wonderful resource. Examples: photography

Finally, hobbyist websites are a wonderful resource. Examples: photography  health is all about nurturing our skills/talents, exploring new pathways, facing new challenges, engaging our minds, and enjoying the “good life” after full-time employment. Nothing is stopping you from starting a new career, learning a new language, writing a book (or reading everything you always wanted to at the library), learning (better) how to act/dance/sing/play a new instrument, taking a trip to a new country (or city in the US) or journey to your backyard with a camera, and modeling the essence of the Robert Frost message, “I took the road less traveled by…. and, that has made all the difference.”

health is all about nurturing our skills/talents, exploring new pathways, facing new challenges, engaging our minds, and enjoying the “good life” after full-time employment. Nothing is stopping you from starting a new career, learning a new language, writing a book (or reading everything you always wanted to at the library), learning (better) how to act/dance/sing/play a new instrument, taking a trip to a new country (or city in the US) or journey to your backyard with a camera, and modeling the essence of the Robert Frost message, “I took the road less traveled by…. and, that has made all the difference.”