Rebuilding instrumental technique after a long break

Director’s Note: This is the week to get ready for the return of the South Hills Junior Orchestra after all our vacations! If you live in the Southwestern PA area, we hope you will consider this a personal invitation to “TRY SHJO” and participate in several free and open rehearsals of our community orchestra – a totally “judgment-free” place for creative self-expression of all ages and ability levels. Practices are held in the Upper St. Clair High School Band (1825 McLaughlin Run Road, Pittsburgh, PA 15241) on Saturdays from 10:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m.

A Google search on my computer fetched the following “AI Overview,” a nearly perfect summary for wind players to recover their “chops” and bring back good tone, intonation, breath support, flexibility of the embouchure, key literacy, and practice habits. For players of all orchestral instrumental sections, I recommend revisiting other articles in the Fox’s Fireside Library to develop a “practice plan” and adopt new musical goals. PKF

To rebuild your brass and woodwind instrumental technique after a long break, focus on the following gradual, three-stage process: first, restore your tone and response, then regain flexibility and dexterity, and finally, rebuild range and endurance. Prioritize short, consistent practice sessions, and avoid pushing too hard too early to prevent injury and bad habits.

Stage 1: Restore tone and response

Your primary goal is to reacquaint your body with the fundamentals of playing by focusing on soft dynamics and your lowest register.

- Breathing exercises: Start without your instrument. Practice deep, diaphragmatic breathing to re-engage your respiratory system and expand your lung capacity. You can use simple routines like inhaling for four counts and exhaling for eight, or try the “pinwheel” exercise to visualize steady airflow.

- Buzzing: Brass players should spend time buzzing with just their mouthpiece to get their lips vibrating efficiently again.

- Long tones: On your instrument, play sustained, steady notes at a soft volume in your lower-to-middle range. Focus on producing a clear, characteristic tone. Use a tuner to monitor your pitch stability.

- Short practice sessions: Limit your initial sessions to 5–20 minutes, with plenty of rest in between. This prevents over-straining your facial muscles and embouchure.

Stage 2: Regain flexibility and dexterity

Once your tone and response feel stable, you can begin to expand your comfortable playing range and improve finger speed.

- Scales and arpeggios: Practice basic scales and arpeggios at a slow, controlled tempo. This helps rebuild muscle memory for your fingers while keeping the focus on even, beautiful tone.

- Slurred partials (brass) and lip slurs (woodwind): Practice smoothly transitioning between notes without using your tongue. This strengthens your embouchure and improves air control.

- Simple music: Play easy, melodic pieces you know well. This helps you focus on phrasing and musicality without the pressure of a difficult score.

- Increase session length gradually: Slowly add time to your practice sessions, perhaps moving to 15–30 minutes at a time. Continue to take frequent breaks.

Stage 3: Rebuild range and endurance

After re-establishing your fundamentals, you can begin to increase the intensity and duration of your playing to return to your previous level.

- Expand your range: Gently start working your way into your upper and lower registers, but maintain a soft dynamic level. Only increase volume once you can play a note softly with a good tone.

- Louder dynamics: Once your full range is accessible, begin practicing with louder dynamics. This is physically demanding, so continue to take frequent rests.

- Articulation: Incorporate tonguing exercises. Start with basic single tonguing before adding more complex techniques like double and triple tonguing.

- Listen to your body: Your body will be the ultimate guide. If you feel any pain or unusual fatigue, ease up and incorporate more rest into your routine.

- Mental preparation and practical tips

- Listen to music: Remind yourself of what inspires you and listen to your favorite players to reconnect with the joy of playing.

- Record yourself: Objectively evaluate your progress by listening back to recordings. This helps you identify areas that need work and celebrate your improvements.

- Revisit old notebooks: Look back at any old lesson journals for useful reminders and insight into your past tendencies.

- Service your instrument: A leaky pad or sticky valve can make returning to your instrument unnecessarily difficult. Have a technician give your instrument a “clean, oil, and adjust” to ensure it’s in prime playing condition.

- Be patient: You are not expected to be at your former playing level immediately. Trust that your muscle memory will return with consistent, smart practice.

Click here to download a printer-friendly copy of this article.

Here are additional resources shared in the SHJO eUPDATE newsletter (August 30, 2025):

- STRINGS and ALL: Watch this video, “How To Get Back Into Playing After A Long Break” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAXmTV0h054

- STRINGS: Peruse the tips and links from “The Strad” website:

https://www.thestrad.com/playing-hub/returning-to-playing-after-a-break-top-string-teachers-share-their-tips/13749.article - BRASS PLAYERS: Read and explore links in this blog post:

https://tsargentmusic.com/2020/08/11/getting-back-after-summer-break-or-any-break/ - CLARINETS (and tips suitable for all wind players): View “Returning to the Clarinet After a… Break”

https://youtu.be/18kJ8OBtrFQ - PERCUSSIONISTS: Read this article by Roland Corp “Getting Back into Drums & Drumming”

https://rolandcorp.com.au/blog/getting-back-into-drums-and-drumming

– AND – view the video “How to Practice After a Long Break” by Rob Knopper

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=80cpExlj4oo&t=133s

PKF

© 2025 Paul K. Fox

Welcome back to our series on music teacher (and other professionals) self-care.

Welcome back to our series on music teacher (and other professionals) self-care. Practice emotional first aid… Do you beat yourself up when you experience failure or make a mistake? [Find] ways to break the negative patterns of thought.

Practice emotional first aid… Do you beat yourself up when you experience failure or make a mistake? [Find] ways to break the negative patterns of thought.

twice as long as the length of the inhale. For example, inhale to the count of four, pause briefly, and exhale to the count of eight. Repeat three times.

twice as long as the length of the inhale. For example, inhale to the count of four, pause briefly, and exhale to the count of eight. Repeat three times.

Her common examples of cognitive distortions include the following. Do any of these sound familiar?

Her common examples of cognitive distortions include the following. Do any of these sound familiar?

Learn something new.

Learn something new.

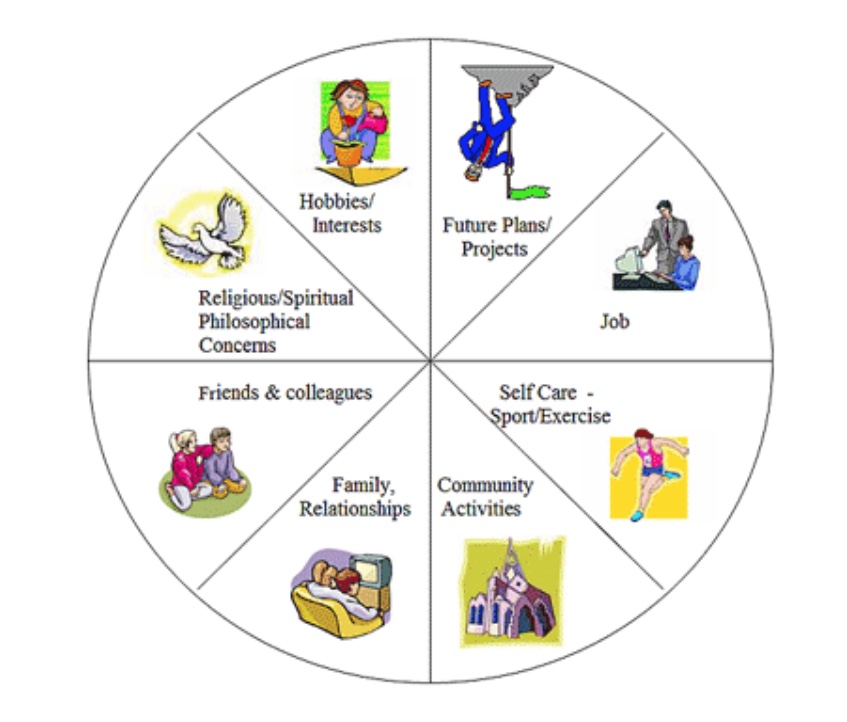

In almost every health and wellness article, we hear the emphasis of prioritizing and seeking a more equitable use of personal time, achieving what Ernie Zelinski, author of the best-selling book How to Retire Happy, Wild, and Free, refers to as “work/life balance.” Future blogs on samples of “super stress reducers” in “setting boundaries,” time management, and innovative organizational tools will be forthcoming.

In almost every health and wellness article, we hear the emphasis of prioritizing and seeking a more equitable use of personal time, achieving what Ernie Zelinski, author of the best-selling book How to Retire Happy, Wild, and Free, refers to as “work/life balance.” Future blogs on samples of “super stress reducers” in “setting boundaries,” time management, and innovative organizational tools will be forthcoming.

Reprinted from the Spring 2016 issue of PMEA News, the state journal of the Pennsylvania Music Educators Association.

Reprinted from the Spring 2016 issue of PMEA News, the state journal of the Pennsylvania Music Educators Association.

If you’ve ever been in a choir, you’ve probably been told that the proper way to sing is from your belly.

If you’ve ever been in a choir, you’ve probably been told that the proper way to sing is from your belly. As the popularity of group singing grows, science has been hard at work trying to explain why it has such a calming yet energizing effect on people. What researchers are beginning to discover is that singing is like an infusion of the perfect tranquilizer, the kind that both soothes your nerves and elevates your spirits.

As the popularity of group singing grows, science has been hard at work trying to explain why it has such a calming yet energizing effect on people. What researchers are beginning to discover is that singing is like an infusion of the perfect tranquilizer, the kind that both soothes your nerves and elevates your spirits. Regular exercising of the vocal cords can even prolong life, according to research done by leading vocal coach and singer Helen Astrid, from The Helen Astrid Singing Academy in London. “It’s a great way to keep in shape because you are exercising your lungs and heart.”

Regular exercising of the vocal cords can even prolong life, according to research done by leading vocal coach and singer Helen Astrid, from The Helen Astrid Singing Academy in London. “It’s a great way to keep in shape because you are exercising your lungs and heart.” Colette Hiller, director of Sing The Nation, is convinced that singing builds social confidence by helping individuals connect to each other, and to their environment. “Think of a football stadium with everyone singing,” she says. “There’s an excitement, you feel part of it, singing bonds people and always has done. There’s a ‘goosebumpy’ feeling of connection.”

Colette Hiller, director of Sing The Nation, is convinced that singing builds social confidence by helping individuals connect to each other, and to their environment. “Think of a football stadium with everyone singing,” she says. “There’s an excitement, you feel part of it, singing bonds people and always has done. There’s a ‘goosebumpy’ feeling of connection.”  Studies have linked singing with a lower heart rate, decreased blood pressure, and reduced stress, according to Patricia Preston-Roberts, a board-certified music therapist in New York City. She uses song to help patients who suffer from a variety of psychological and physiological conditions.

Studies have linked singing with a lower heart rate, decreased blood pressure, and reduced stress, according to Patricia Preston-Roberts, a board-certified music therapist in New York City. She uses song to help patients who suffer from a variety of psychological and physiological conditions. The seniors involved in the chorale (as well as seniors involved in two separate arts groups involving writing and painting) showed significant health improvements compared to those in the control groups. Specifically, the arts groups reported an average of:

The seniors involved in the chorale (as well as seniors involved in two separate arts groups involving writing and painting) showed significant health improvements compared to those in the control groups. Specifically, the arts groups reported an average of: Okay, besides that crack about “elderly” in that last article (we’re not “old,” yet!), the evidence seems conclusive! For our general health, feelings of well-being, improved social connections, and “just having fun,” we should all be motivated TODAY to go out and find a community choir and start singing regularly in a group. Enough said?

Okay, besides that crack about “elderly” in that last article (we’re not “old,” yet!), the evidence seems conclusive! For our general health, feelings of well-being, improved social connections, and “just having fun,” we should all be motivated TODAY to go out and find a community choir and start singing regularly in a group. Enough said? For both the instrumental and choral groups, we are most thankful to the contributions of our “dream team” of PMEA researchers and editors (as of April 13, 2016): Jan Burkett, Craig Cannon, Jo Cauffman, Deborah Confredo, Susan Dieffenbach, Timothy Ellison, Paul Fox, Joshua Gibson, Rosemary Haber, Estelle Hartranft, Betty Hintenlang, Ada Jean Hoffman, Thomas Kittinger, Chuck Neidhardt, Sarah Riggenbach, Ron Rometo, Joanne Rutkowski, Marie Weber, Lee Wesner, and Terri Winger-Wittreich. We are especially grateful to the efforts of Director of Member Engagement Joshua Gibson who located the counties and e-mail addresses in the choir directory.

For both the instrumental and choral groups, we are most thankful to the contributions of our “dream team” of PMEA researchers and editors (as of April 13, 2016): Jan Burkett, Craig Cannon, Jo Cauffman, Deborah Confredo, Susan Dieffenbach, Timothy Ellison, Paul Fox, Joshua Gibson, Rosemary Haber, Estelle Hartranft, Betty Hintenlang, Ada Jean Hoffman, Thomas Kittinger, Chuck Neidhardt, Sarah Riggenbach, Ron Rometo, Joanne Rutkowski, Marie Weber, Lee Wesner, and Terri Winger-Wittreich. We are especially grateful to the efforts of Director of Member Engagement Joshua Gibson who located the counties and e-mail addresses in the choir directory.