The Life Cycle of a Successful & Happy Music Educator

“There are no secrets to success. It is the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure.”

Colin Powell

I feel blessed to have spent five decades in the field of music education. No other career has offered so much personal satisfaction, discoveries and growth of hidden potentials and skills I never knew I had, sharing my love of creative self-expression, and facilitating others to seek their own connections to music. I am trying to follow my own “retirement” advice, remaining active in the profession in ways that matter, helping others find their own success, and embracing author Ernie Zelinski’s mantra to “find purpose, structure, and community” throughout my years as a retiree.

Parallel to the mission of the Pennsylvania Music Educators Association Council for Teacher Training, Recruitment, and Retention, serving “the life cycle of a music educator,” this blog site is my “gift” to future and current music educators and those contemplating retirement. Recently, I presented a workshop on this topic for student teachers in music education at Seton Hill University (Westmoreland County, Greensburg, PA), summarizing a framework for “professional development for life” in order to foster these goals and nurture meaningful successes of pre-service music educators. No “road map” (or to retain the analogy in my title, “library” of resources) is applicable to everyone nor will the journeys/readings be the same… but since my collections of past blogs over ten years are now vast, I offer this simplified checklist for any “newbie” interested to seek their own pathway. Happy travels!

- Preservice/Training Years: Marketing, Interviewing, & Networking

- Rookie/Practicing Years: Ethics & Professionalism 101

- Inservice/Growing Years: Career Development (next blog post)

- Veteran/Sustaining Years: Time Management & Self-Care (next blog post)

- Next Chapter/Living the Dream Years: Retirement Prep & Mastery (next blog post)

The slides to the entire presentation are open to anyone to view below.

However, here’s a shamelessly offered advertisement. It would make more sense to see this “in-person” or online with my moderation. I would be happy to present this session (giving me at least an hour to allow for more interactive discussion) to collegiate members, a music education methods class, a regional workshop, or festival meeting via Zoom or in-person (in PA). If interested or to inquire, please send me an email here.

Now… the checklists. Depending on your current status and interests, peruse the following resources. It is possible a few of the links contained within these blogs have gone inactive, but I believe enough is there for you to gain the insight, tools and motivation to achieve “professional development for life.”

Stage 1 – Preservice/Training Years

The focus during our early years in any profession is learning the “shtick” and getting ready for the job search and interviewing. Probably before anything, we revisit our inspiration and what Simon Sinek directs us to “the why” of any organization… in this case, “the why” of becoming a music educator – our philosophy, mission, vision, and understanding of the purpose/role of music education n the schools.

[ ] 1. The Meaning of Pro: Are you a professional? Do you have the skills, habits, and attitudes of a professional in the field of education?

[ ] 2. Marketing Yourself and Your Pre-K to 12 Music Certification: What is your professional “brand?” Do you plan to “sell” yourself as a specialist, e.g., “band director” or “elementary general music teacher, etc.? To those potential job candidate screeners, promote the image of being proficient – “a total music educator” – and don’t emphasize your major/emphasis or perceived skill or experience limitations. The only thing that really matters is whether you are the “right fit” for a particular opening, and of course, deciding whether or not to accept the offer. Your license (certification) implies that you do indeed have the necessary training to teach all K-12 music classes. Don’t sell yourself short!

[ ] 3. Criteria for Selection of the “Ideal” Teacher Candidate: The best way to prepare for a job interview is to become aware of how you will be judged in comparison with your peers. What are the standards (or behaviors or criteria) of outstanding teachers? For what are administrators looking to fill the vacancies and build/maintain a quality staff?

[ ] 4. “S” is for Successful Storytelling: The number one method to land a job is “SHOW, don’t TELL!” Stories are up to 22 times more effective than facts alone. Identify the key impressions you want to convey. Pick interview stories that will “sell” the right message. Learn how to share unique personal examples of your interactions with children, colleagues, and music programs. These additional resources can be shared about “strategic storytelling” and how to prepare (a.k. practice) telling your anecdotes:

- “Harnessing the Power of Stories” by Jennifer Aaker, Professor of Marketing at the Stanford Graduate School of Business

- How to Effectively Use Storytelling in Interviews by Bill Baker

[ ] 5. The Ultimate Interview Primer for Pre-Service Music Teachers: This super-packet has a collection of more tips on marketing yourself and mastering the “science” of finding a job, interview strategies and sample questions, evaluative rubrics, follow-ups, “bad habits” to avoid, etc. Take the time to download and explore these excellent tools!

Homework for Stage 1 – Developing a Marketing Plan

- Standards: Define your personal mission, goals, and philosophy for teaching music, modeling the highest ideals of professionalism, and becoming the “total music educator.”

- Marketing: Design and distribute a “state-of-the-art” résumé, e-portfolio, website, and business card.

- Skills: Compile a list of anecdotes and true stories of you overcoming challenges, solving problems, and demonstrating “best practices” of professionalism and self-improvement.

- Assessment: Practice, record, and evaluate yourself answering job interview questions.

Stage 2 – Rookie/Practicing Years

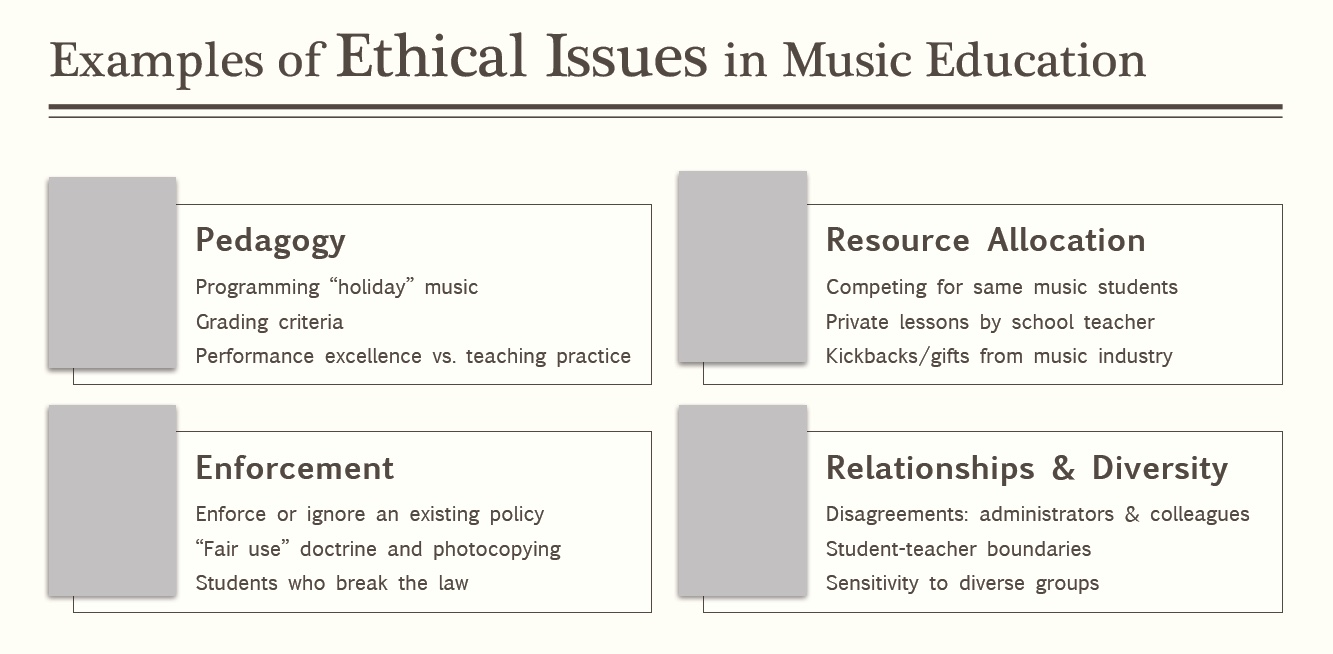

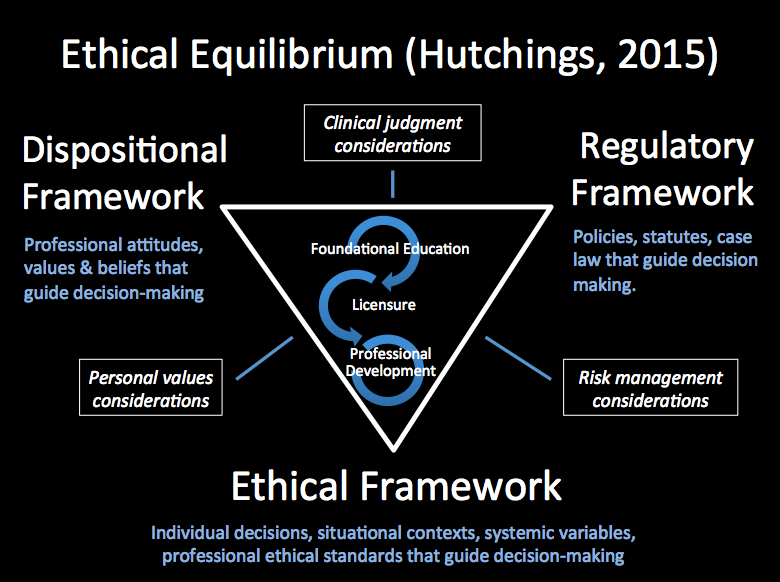

[ ] 6. Ethics for Music Educators – Part I, Part II, and Part III: You may think that the primary focus for our early years as a novice teacher would be the reinforcement of what we learned about education – curriculum, content, methods, classroom management, and assessment, but something else trumps all! Before we ever step foot in a classroom, rehearsal room, or stage, it is essential we first review those ethical standards in education, terminology, philosophy, and “the codes” that bind us. We should be able to show in depth understanding of these concepts:

- Fiduciary

- Moral Standard

- Ethical Standard

- Ethical Equilibrium

- Moral Professionalism

- Differences Between a Code of Conduct and a Code of Ethics

- Student-Teacher Boundaries and the Slippery Slope of Ambiguous Relationships

- Function/Relevance of “The Codes” to Daily Teacher Decision-Making

For nearly every presentation I do on “ethics for pre-service music educators,” I hold up a fifty dollar bill and ask, “Who wants this? Can you name the exact title of your state’s code of conduct for educators and the government agency that enforces it?” So far, no one has made me $50 poorer. Indeed, few active teachers “in the trenches” have read their “codes,” and frankly, that is surprising. Violation of any major provision in our code of conduct will result in a serious reprimand, being fired, losing one’s certificate to teach anywhere, and/or criminal/civil prosecutions. Wouldn’t you think all of us would be intimately familiar with the “rules” of our professional?

For my Pennsylvania colleagues, please download and READ these:

- PA Professional Practices and Standards Commission

- PA Code of Professional Practice and Conduct

- PA Educator Discipline Act

- PA Educator Ethics Toolkit

- Model Code of Ethics for Educators

[ ] 7. Ethical Scenarios (and More): The study of morality in professional decision-making is essential to pre- and in-service training of music teachers. Our goal should be to reinforce recommendations for the avoidance of inappropriate behavior (or even the appearance of impropriety), and defining and modeling the “best practices” of a serving as a “fiduciary” by promoting trust, fostering a safe environment for learning, acting in the best interests of our students, and upholding the overall integrity of the profession.

One of the best ways to accomplish this is to discuss ethical scenarios in small peer groups, an interactive exchange of opinions – “what would you do?” – in analyzing hypothetical case studies. Perhaps in a college methods class, student teaching seminar, department meeting, faculty committee, or PLC (Professional Learning Community), the following thought-provoking questions from the Facilitator Guide for Professional Responsibilities – Module 5, written by the Connecticut State Department of Education T.E.A.M. (Teacher Education & Mentoring) manual should be discussed in an open, reflective, nonthreatening setting:

- What possible issues/concerns might this scenario raise?

- How could this situation become a violation of the law, the “Code” or other school/district policies?

- In this situation, what are some potential negative consequences for the teacher, students, parents, and/or school staff?

- How would this episode affect a teacher’s efficacy in his/her classroom, demean the employing school entity, or damage her position as a moral exemplar in the community?

Please visit link #7 (above) for sources of ethical scenarios to study, including my “conundrum series.”

Homework for Stage 2 – Are you an Ethical Educator?

- Self-assess your own habits of professionalism, and identify goals for at least two “personal improvement projects.”

- Read “cover-to-cover” any documents relating to your own state’s code of conduct and the NASDTEC Model Code of Ethics for Educators.

- Discuss the ramifications of “choices” and teacher decision-making in context by reading a few of the fictitious scenarios highlighting ethical precautions, disputes, and “conundrums.”

Coming Soon…

Bookends Part Two

PKF

© 2023 Paul K. Fox

Administrators, parents and public’s interpretation of “separation of church and state” or “perceived emphasis” on Holiday vs. Christmas music (with sacred text) at December concerts e.g. Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus, Hatikvah, and/or John Rutter’s Oh Come All Ye Faithful & Joy to the World as the finale

Administrators, parents and public’s interpretation of “separation of church and state” or “perceived emphasis” on Holiday vs. Christmas music (with sacred text) at December concerts e.g. Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus, Hatikvah, and/or John Rutter’s Oh Come All Ye Faithful & Joy to the World as the finale

Competition for the enrollment of the same students (band/string/choir) within the music department

Competition for the enrollment of the same students (band/string/choir) within the music department

If you have not had the occasion to read Case Studies in Music Education by Frank Abrahams and Paul D. Head, it would be a valuable aid to “facilitate dialogue, problem posing, and problem solving” among pre-service (and current) music teachers. Using the format of Introduction, Exposition, Development, Improvisation, and Recapitulation known by all music professionals, each chapter presents a scenario with a moral dilemma that many music educators face in the daily execution of their teaching responsibilities.

If you have not had the occasion to read Case Studies in Music Education by Frank Abrahams and Paul D. Head, it would be a valuable aid to “facilitate dialogue, problem posing, and problem solving” among pre-service (and current) music teachers. Using the format of Introduction, Exposition, Development, Improvisation, and Recapitulation known by all music professionals, each chapter presents a scenario with a moral dilemma that many music educators face in the daily execution of their teaching responsibilities. For additional examples of ethical issues in education, try these links. Personally, many of these fictional video reenactments are hardcore and very painful to view… but may shed some light in any discussion of teacher (mis)behavior: actions from simply inappropriate, unwise, or “bad for appearances” to a range (from bad to worst) of unprofessional, immoral, unethical, and illegal conduct. Some of these stories you will agree should be instantly labeled as the highest degree of unethical practice ― actual “crimes against children” and should invoke punishment if found guilty ― while others may lack clarity and make it difficult in arriving to a consensus.

For additional examples of ethical issues in education, try these links. Personally, many of these fictional video reenactments are hardcore and very painful to view… but may shed some light in any discussion of teacher (mis)behavior: actions from simply inappropriate, unwise, or “bad for appearances” to a range (from bad to worst) of unprofessional, immoral, unethical, and illegal conduct. Some of these stories you will agree should be instantly labeled as the highest degree of unethical practice ― actual “crimes against children” and should invoke punishment if found guilty ― while others may lack clarity and make it difficult in arriving to a consensus.

Many have suggested that there has been a decline in moral standards that have contributed to ethical disputes in modern society (and in the public schools). Some say that this is attributed to a breakdown or lessening of the influence of organized religion and family values. “When Cultures Shift,” an excellent article in the New York Times (April 17, 2015), David Brooks explores some of causes and effects of this “slip” to our value systems, ethics, and renewed focus on self:

Many have suggested that there has been a decline in moral standards that have contributed to ethical disputes in modern society (and in the public schools). Some say that this is attributed to a breakdown or lessening of the influence of organized religion and family values. “When Cultures Shift,” an excellent article in the New York Times (April 17, 2015), David Brooks explores some of causes and effects of this “slip” to our value systems, ethics, and renewed focus on self: Do schools, not necessarily families, serve as the “safety net” for socializing its citizens, and teaching morality, manners, and the values of human relationships? Are teachers held to a higher standard of behavior in order to model these principles and charged with the responsibility of indoctrinating the meaning of “right and wrong” and how to get along with each other? Many would seem to agree, including sample codes of ethics for teachers and this from Robert Fulghum

Do schools, not necessarily families, serve as the “safety net” for socializing its citizens, and teaching morality, manners, and the values of human relationships? Are teachers held to a higher standard of behavior in order to model these principles and charged with the responsibility of indoctrinating the meaning of “right and wrong” and how to get along with each other? Many would seem to agree, including sample codes of ethics for teachers and this from Robert Fulghum  In Essays on Moral Development: The Philosophy of Moral Development (New York: Harper Collins 1981), Lawrence Kohlberg illustrates his “Six Stages of Moral Development” from ethical decisions based on adherence to rules/regulations and avoidance of punishment to acceptance of universal principles of justice and respect for human life.

In Essays on Moral Development: The Philosophy of Moral Development (New York: Harper Collins 1981), Lawrence Kohlberg illustrates his “Six Stages of Moral Development” from ethical decisions based on adherence to rules/regulations and avoidance of punishment to acceptance of universal principles of justice and respect for human life. As I said in Part I of this blog series, one of the first acts of a new or transferred teacher upon being hired to a specific school district is to visit the website of his/her state’s education department, and make a thorough search on the topic of “code of ethics” or “code of conduct.” There is no defense for ignorance of the codes and statutes relevant to the state you are/will be employed.

As I said in Part I of this blog series, one of the first acts of a new or transferred teacher upon being hired to a specific school district is to visit the website of his/her state’s education department, and make a thorough search on the topic of “code of ethics” or “code of conduct.” There is no defense for ignorance of the codes and statutes relevant to the state you are/will be employed.

In addition, in almost every state education system, there are “mandatory reporting” regulations. Teachers are held responsible to ensure that their colleagues conform to the appropriate standards of ethical practice as well. In other words, if you know something is wrong and you do not report it to an administrator, you could also be liable and subject to hearings, discipline, and even prosecutions for negligence of your duty to protect the best interests, health, and safety of the student(s) involved.

In addition, in almost every state education system, there are “mandatory reporting” regulations. Teachers are held responsible to ensure that their colleagues conform to the appropriate standards of ethical practice as well. In other words, if you know something is wrong and you do not report it to an administrator, you could also be liable and subject to hearings, discipline, and even prosecutions for negligence of your duty to protect the best interests, health, and safety of the student(s) involved. A sense of invulnerability

A sense of invulnerability It is the responsibility of the teacher to control his or her “public brand” – how he or she wants to be perceived by students, parents, colleagues, and the public. One’s public brand can and does impact perceptions, which in turn can impinge upon effectiveness.

It is the responsibility of the teacher to control his or her “public brand” – how he or she wants to be perceived by students, parents, colleagues, and the public. One’s public brand can and does impact perceptions, which in turn can impinge upon effectiveness.