Don’t you love this quote from TeachThought?

“Teaching isn’t rocket science; it’s harder!”

Teachers make as many as 1,500 decisions a day for their classes and students… that’s as many as four educational choices per minute for the average teacher given six hours of class time. Surprised? (Not if you are an educator!) Check out this corroborating research:

- How Many Decisions Do Teachers Make Every Day? by Steven M. Singer

- The Best Research on How Many Decisions a Teacher Makes Each Day by Larry Ferlazzo

- Jazz, Basketball, and Teacher Decision-making by Larry Cuban

- Battling Decision Fatigue by Gravity Goldberg and Renee House (Edutopia)

Of course it can be exhausting… and as fast as “things” happen, even mind-numbing at times!

What do educators rely on for guidance, a sort of internal “ethical compass” for making these decisions, many of which are snap judgments?

- Educational background

- Teacher “chops” (professional experience)

- Peer and administrative support

- Personal moral code (derived from one’s life experiences and upbringing)

- Aspirations, values, and beliefs generally agreed upon by educational practitioners

- State’s code of conduct and other regulations, statutes, policies, and case law

- Professional ethics

Or all of the above?

At this juncture during my workshops on ethics, I usually quote Dr. Oliver Dreon, Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the Digital Learning Studio at Millersville University of Pennsylvania and one of the authors of the Educator Ethics and Conduct Tool Kit of the Pennsylvania Professional Standards and Practices Commission:

“From a decision-making standpoint, I tend to look at it from the perspective of Ethical Equilibrium (work by Troy Hutchings). Teachers weigh the moral (personal) dimensions with regulatory ones (the law) with the ethics of the profession… While focusing on consequences is important, I worry that teachers may interpret this to mean that as long as they don’t break the law, they can still be unprofessional and immoral.”

– Dr. Oliver Dreon

From college students participating in their first field observations to rookie teachers (and even veterans in the field), I recommend searching the term “ethics” on the website of your State Board of Education. In Pennsylvania, checkout the following:

- PA Professional Standards and Practices Commission (PSPC)

- PSPC Ethics and Conduct Tool Kit

- Pennsylvania Department of Education

- The Ethical Educator and Professional Practices – Frequently Asked Questions

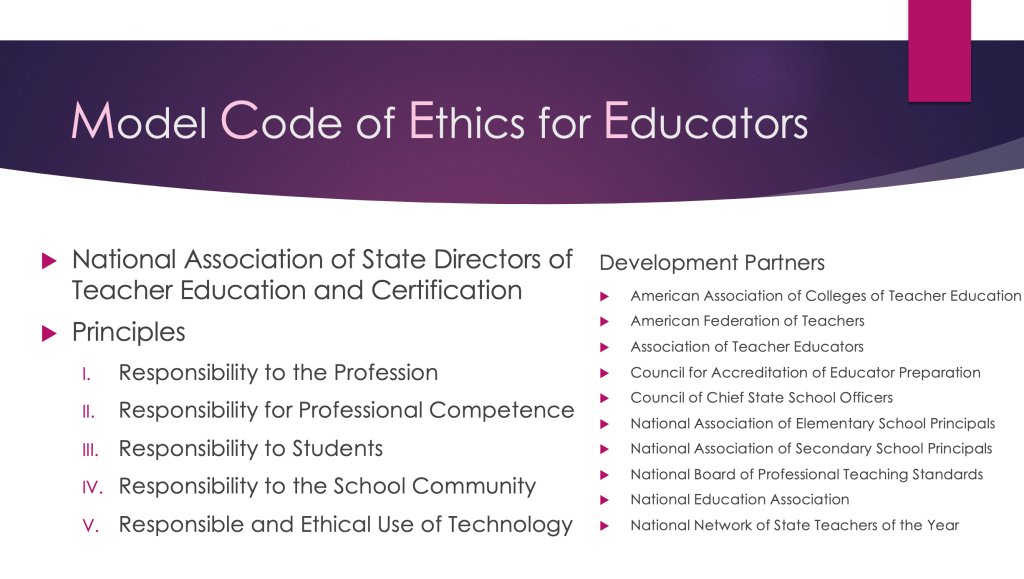

Now enters probably the single most valuable document of our time, an all-encompassing philosophy for embracing the highest standards of what it means to be an ethical educator: the Model Code of Ethics for Educators (MCEE), developed under the leadership of the National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification (NASDTEC). With the collaboration of numerous development partners including the American Federation of Teachers, National Education Association, National Association of Elementary School Principals, National Association of Secondary School Principals, Council of Chief State School Officers, and American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education – to name a few – MCEE is comprised of five core principles (like spokes in a wheel – all with equal emphasis), 18 sections, and 86 standards.

“The purpose of the Model Code of Ethics for Educators (MCEE) is to serve as a shared ethical guide for future and current educators faced with the complexities of P-12 education. The code establishes principles for ethical best practice, mindfulness, self-reflection and decision-making, setting the groundwork for self-regulation and self-accountability. The establishment of this professional code of ethics by educators for educators honors the public trust and upholds the dignity of the profession.”

– MCEE Framing Document

Although pre- and in-service training on both are essential, the differences between a “code of conduct” and a “code of ethics” are vast. Codes of conduct like the Code of Professional Practice and Conduct for Pennsylvania teachers are specific mandates and prohibitions that govern educator actions. A code of ethics is a set of principles that guide professional decision making, not necessarily issues of “right or wrong” (more shades of grey) nor defined in exact terms of law or policies. Codes of ethics are more open-ended, a selection of possible choices, usually depended on the context or circumstances of the situation.

“The interpretability of The Model Code of Ethics for Educators allows for robust professional discussions and targeted applications that are unique to every schooling community.”

– Troy Hutchings, Senior Policy Advisor, NASDTEC

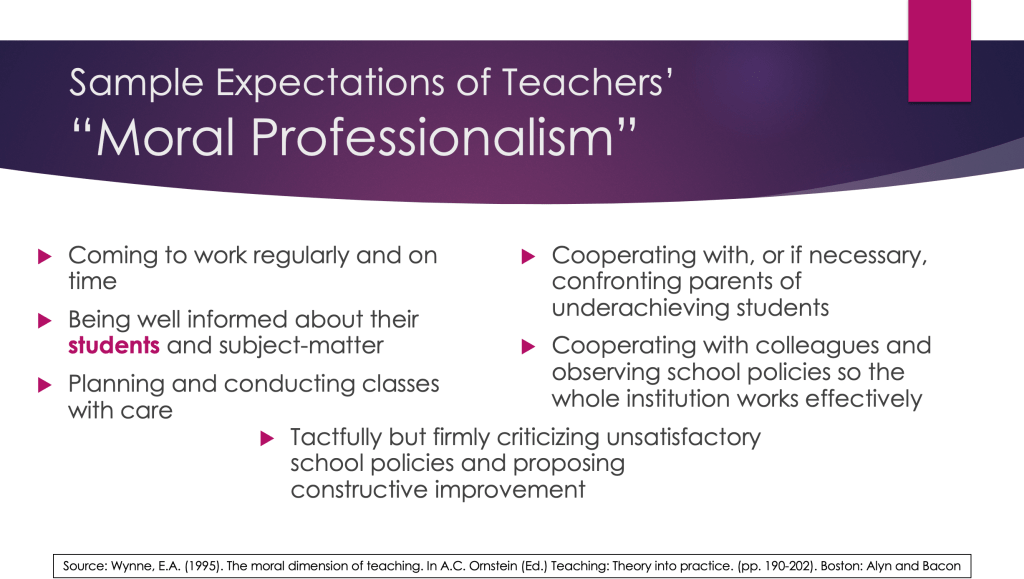

The music teacher and administrator colleagues with whom I have been privileged to work for more than 40 years are highly dedicated and competent visionaries who focus on “making a difference” in the lives of their students, modeling “moral professionalism” and the highest ethical standards for their classes, schools, and communities, in support of maintaining the overall integrity of the profession.

However, let’s unpack some of “the wisdom” of MCEE as it addresses the rare “nay-sayers” and entrenched teacher attitudes, failing to understand “the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do…” (Potter Stewart) or “doing the right thing when no one else is watching – even when doing the wrong thing is legal” (Aldo Leopold).

Here are sample negative responses, MCEE “exemplars,” and proposed assimilations for thoughtful and interactive peer discussion. Bring these to your next staff meeting or workshop, and apply them to a few mock scenarios (like these from my past blog ).

Principle I: Responsibility to the Profession

The professional educator is aware that trust in the profession depends upon a level of professional conduct and responsibility that may be higher than required by law. This entails holding one and other educators to the same ethical standards.

“I didn’t know it was wrong…”

Section I, A, 1: Acknowledging that lack of awareness, knowledge, or understanding of the Code is not, in itself, a defense to a charge of unethical conduct;

My comment: The old adage, “ignorance of the law is no excuse for breaking it.” – Oliver Wendell Holmes

“What’s the problem? I didn’t break the law!

MCEE Section I, A, 5: Refraining from professional or personal activity that may lead to reducing one’s effectiveness within the school community;

My comment: Any on or off-duty conduct or inappropriate language that undermines a teacher’s efficacy in the classroom, damages his/her position as a “moral exemplar” in the community, or demeans the employing school entity may result in loss of job, suspension or revocation of license, and/or other disciplinary sanctions.

“I’m not a rat fink…”

MCEE Section I, B, 2: Maintaining fidelity to the Code by taking proactive steps when having reason to believe that another educator may be approaching or involved in an unethical compromising situation;

My comment: As a professional with “fiduciary” responsibilities, we must look out for the welfare of our students, proactively protecting them from harm by embracing all provisions of “mandatory reporting.”

“What’s in it for me?”

MCEE Section I, C, 3: Enhancing one’s professional effectiveness by staying current with ethical principles and decisions from relevant sources including professional organizations;

MCEE Section I, C, 4: Actively participating in educational and professional organizations and associations;

My comment: Keeping up-to-date and current, we are fortunate to avail ourselves with the exhaustive tools and resources of media, music, and methods provided by groups like the Pennsylvania Music Educators Association and National Association for Music Education.

Principle II: Responsibility for Professional Competence

The professional educator is committed to the highest levels of professional and ethical practice, including demonstration of the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required for professional competence.

“What’s the big deal about standards?”

Section II, A, 1: Incorporating into one’s practice state and national standards, including those specific to one’s discipline;

My comment: As professionals, we should volunteer to help write our school’s courses of study, content units, and learning goals for the subjects we teach, and take advantage of the National Core Arts Standards, the PMEA Model Curriculum Framework, and the state’s standards.

“Not another ‘flavor-of-the-month’ in-service program!”

Section II, A, 5: Reflecting upon and assessing one’s professional skills, content knowledge, and competency on an ongoing basis;

Section II, A, 6: Committing to ongoing professional development

My comment: Always “raising the bar,” being a member of a “profession” (like medical personnel, counselors, attorneys, etc.) requires the loftiest benchmarks of self-regulation and assessment, ongoing training, retooling, and self-improvement plans, revision and enforcement of “best practices,” and application of 21st Century learning skills.

“I needed to give him credit?”

MCEE Section II, B, 1: Appropriately recognizing others’ work by citing data or materials from published, unpublished, or electronic sources when disseminating information;

My comment: Especially during this period of online/virtual/remote education brought on by COVID-19, we must reference the owners of intellectual property (including sheet music) that we use and abide by all copyright regulations. In general, it is always “best practice” to cite research or authorship “giving credit where credit is due!”

“I’m just a music teacher! Don’t ask me to do anything else!”

MCEE Section II, C, 2: Working to engage the school community to close achievement, opportunity, and attainment gaps;

My comment: We teach “the whole child,” not a specialty or specific content area! I believe our ultimate mission is to facilitate our students’ capacity and desire to learn, inspire self-direction and self-confidence, and foster future success in life.

Principle III: Responsibility to Students

The professional educator has a primary obligation to treat students with dignity and respect. The professional educator promotes the health, safety, and well being of students by establishing and maintaining appropriate verbal, physical, emotional, and social boundaries.

“It’s just a gift…”

MCEE Section III, A, 5: Considering the implication of accepting gifts from or giving gifts to students;

My comment: It is not appropriate to give a gift to a student lacking an educational purpose. In some cases, this may be defined as a “sexual misconduct.” It begs the larger question: “Do you ensure that all of your interactions with students serve an educational purpose and occur in a setting consistent with that purpose?” Also from the PA Professional Standards and Practices Commission: “Teachers should refrain from accepting gifts or favors that might impair or appear to impair professional judgment.”

“You should never touch a student!”

MCEE Section III, A, 6: Engaging in physical contact with students only when there is a clearly defined purpose that benefits the student and continually keeps the safety and well-being of the student in mind;

My comment: We were told this warning in methods classes. However, as I mentioned in a previous blog here, this “rule” has little support in research or common “best practices.” It has been my experience that on occasion, most elementary instrumental teachers assist their students in acquiring the correct playing posture and hand positions by using some (limited) physical contact. Consoling an upset student with a pat on the shoulder is not out-of-line either. The factors that may contribute to the moment being judged “okay” vs. “inappropriate” boil down to:

- Intent

- Setting

- Length of time

- Frequency or patterns of repetition

- Comfort level of the student

- Age level of the student

- Happening in public

- Who started it?

“My students are my friends!”

MCEE Section III, A, 7: Avoiding multiple relationships with students which might impair objectivity and increase the risk of harm to student learning or well-being or decrease educator effectiveness;

My comment: You cannot be their “friend.” You are their teacher, an authority figure that is looking out for them and doing what is necessary (“fiduciary” responsibilities) for their health and welfare… perhaps at times things they do not want you to do. Crossing the teacher/student boundary with familiarity, informality, and being their “confidant” or “friend” are more than just unprofessional acts – they can foster a dual relationship where roles are less defined, an ambiguity that may lead to additional inappropriate actions and educator misconduct.

“He’s weird…” or “He’s not one of us!”

MCEE Section III, B, 2: Respecting the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of each individual student including, but not limited to, actual and perceived gender, gender expression, gender identity, civil status, family status, sexual orientation, religion, age, disability, race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and culture;

My comment: Check your prejudices and personal biases at the door. Being a teacher is all about sensitivity and caring of all individuals – students, parents, staff, etc. Embracing today’s focus on reprogramming community attitudes on “diversity,” an educator daily models the values of empathy, compassion, acceptance, and appreciation, not just settling with the “lower bar” of tolerance, allowance, and compliance!

“Wait ’til you hear what happened in class today!”

MCEE Section III, C, 1: Respecting the privacy of students and the need to hold in confidence certain forms of student communications, documents, or information obtained in the course of practice;

My comments: Gossiping about and “carrying tales” home or in the teachers’ room are serious breaches of the care and trust as well as your fiduciary responsibilities assigned to you on behalf of your students. As for “regulations,” your indiscretion may be a violation of your students’ confidentiality rights (“a federal crime” according to Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, Grassley Amendment, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act). You are only permitted to share information about a student with another teacher, counselor, or administrator who is on a “needs-to-know” basis or is actively engaged in helping this student.

Principle IV: Responsibility to the School Community

The professional educator promotes positive relationships and effective interactions with members of the school community while maintaining professional boundaries.

“Don’t tell my parents!”

MCEE Section IV, A, 1: Communicating with parents/guardians in a timely and respectful manner that represents the students’ best interests;

My comment: I wish I had a nickel every time a student plead with me, “Don’t call my mom!” It is part of “moral professionalism,” your “code,” and good ethical standards to originate meaningful two-way dialogue, and if necessary, confront the parents of underachieving children. I also believe it goes on long way to nurture your relationships in the community if you notify parents when their kid has done something remarkable… “I caught him being good” or “The improvement has been extraordinary!”

“Did you hear what a staff member said about you… in front of the kids?”

MCEE Section IV, B, 1: Respecting colleagues as fellow professionals and maintaining civility when differences arise;

MCEE Section IV, B, 2: Resolving conflicts, whenever possible, privately and respectfully, and in accordance with district policy;

My comment: Before you bring up the matter with your supervisor or building administrator (which you have the right and even responsibility to do, especially if the students hear any improper speech first-hand or that the incidents rise to the level of bullying or aggressive behavior), first confirm the story. Talk to the unhappy team member one-on-one. Be calm and sensitive, but hold your ground: you must assert that his/her behavior/language is unacceptable and will not be tolerated in the future.

“Not another TEAM meeting?”

MCEE Section IV, B, 4: Collaborating with colleagues in a manner that supports academic achievement and related goals that promote the best interests of students;

My comment: We work together to insure that all educational goals are met. Open and interactive peer partnerships are helpful in the review, design, and application of new lessons, methods, media, and music.

“I was just teasing her…”

MCEE Section IV, B, 8: Working to ensure a workplace environment that is free from harassment.

My comment: Be extremely careful in the practice of any behavior or language of a kidding, sarcastic, cynical, or joking manner. It can be misinterpreted regardless of your intentions… and it can hurt someone’s feelings. And it is never appropriate or “professional” to “put down” another person.

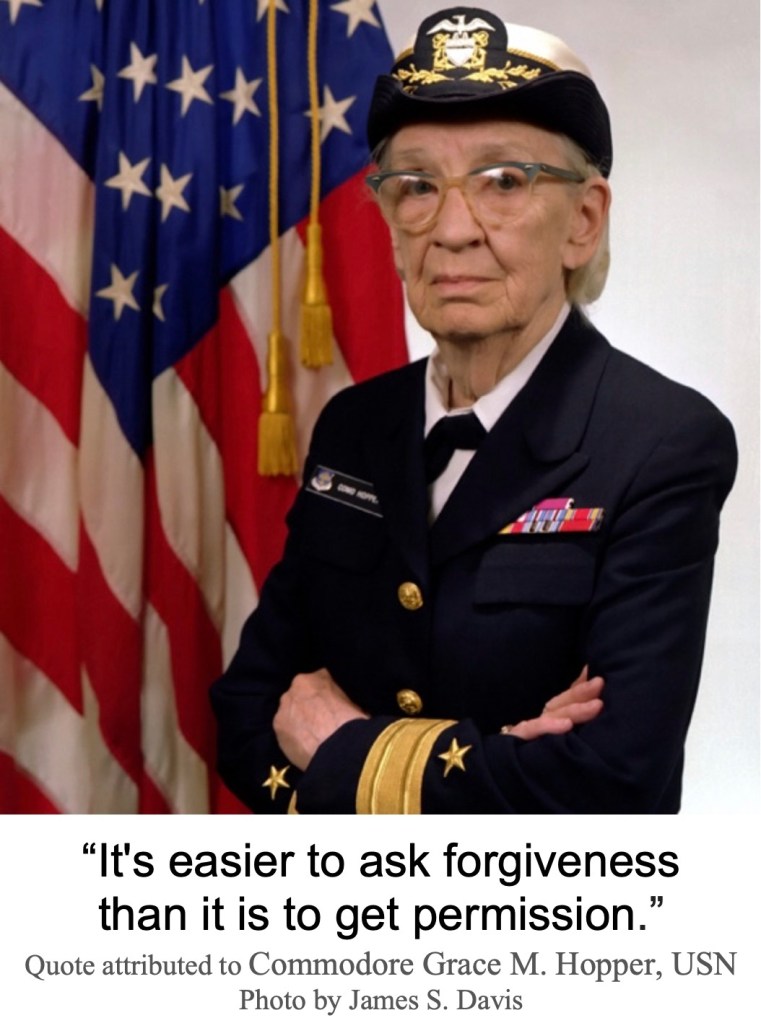

“Don’t ask for permission… beg for forgiveness.”

MCEE Section IV, C, 3: Maintaining the highest professional standards of accuracy, honesty, and appropriate disclosure of information when representing the school or district within the community and in public communications;

My comment: Yes, I have heard this “view” a lot, advocates of whom will tell you to go ahead and stick your neck out to do something “for the good of the order,” and if needed later, “beg for forgiveness” if you decision is met with disapproval from administration. My advice? Less experienced teachers, run everything through your fellow colleagues (informally) and principal (formally). Don’t fall back on the lame “oops” and “beg for forgiveness.” I may have felt differently when I had three times as many years of experience under my belt than the supervisors who were assigned to “manage” me… but, even then, “venturing out without a paddle” usually did not serve the best interests of the students. There’s no reason to place “the teacher’s convenience” over the safety/welfare of the students. Besides, why not take advantage of the legal and political backup of your bosses if they are kept “in the loop?”

“He’s our preferred dealer and always takes care of us.”

MCEE Section IV, D, 4: Considering the implications of offering or accepting gifts and/or preferential treatment by vendors or an individual in a position of professional influence or power;

My comment: Formerly called “sweetheart deals” with music companies, you are on “shaky” ethical ground (and may also have “crossed the line” violating state laws/statutes) if you negotiate the rights of exclusive access to your school’s or booster’s purchasing. If you have any questions about your school’s policy on outside vendors, seek advice from your district’s business manager.

Principle V: Responsible and Ethical Use of Technology

The professional educator considers the impact of consuming, creating, distributing, and communicating information through all technologies. The ethical educator is vigilant to ensure appropriate boundaries of time, place, and role are maintained when using electronic communication.

“Isn’t use of social media forbidden?”

MCEE Section V, A, 1: Using social media responsibly, transparently, and primarily for purposes of teaching and learning per school and district policy. The professional educator considers the ramifications pf using social media and direct communications via technology on one’s interactions with students, colleagues, and the general public.

My comment: Professional educators’ use of a dedicated website or other social network application enables users to communicate with each other by posting information, comments, messages, images, etc. and “learn” together. However, using social media for sharing social interactions and personal relationships with your students, parents, and staff is unethical and dangerous. As they say, “a post (or snap) is forever.” Communicating digitally or electronically with students may lead to the blurring of appropriate teacher-student boundaries and create additional challenges to maintaining and protecting confidentiality.

The Final Word

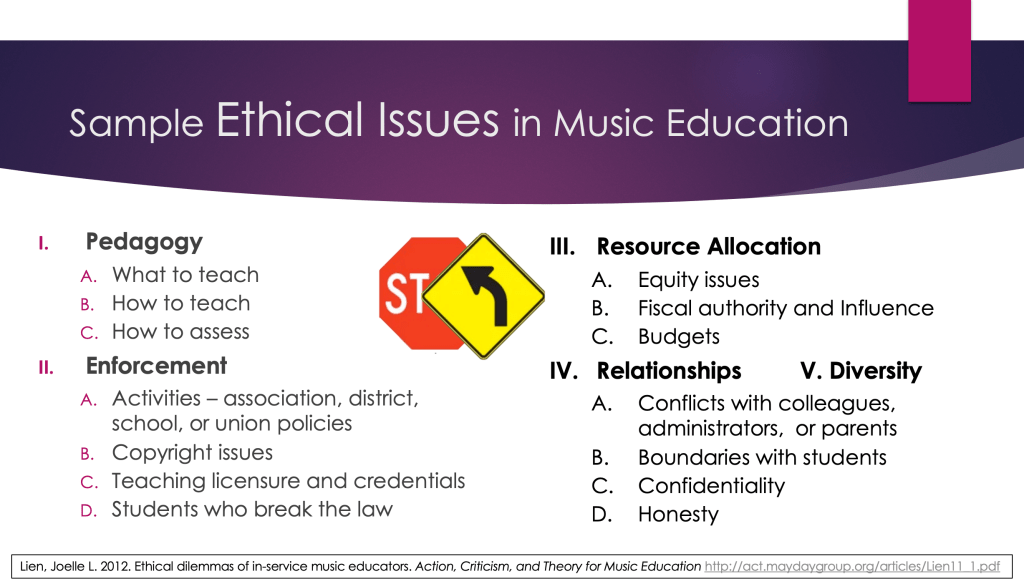

In Pennsylvania (as well as the rest of the country), the statistics on school staff misconduct reports are rising alarmingly. Your own state’s “code of conduct” and the MCEE should help to clarify misunderstandings, but it has been my experience that the majority of educators do not receive regular collegiate, induction, or in-service training on educator ethics or moral professionalism. Luckily, we are fortunate to have access to many mock scenarios (see below) from state departments of education to review/discuss among ourselves common ethical conflicts and “conundrums” dealing with pedagogy, enforcement, resource allocation, relationships, and diversity. We all need to “refresh” our understanding of these issues from time to time and revisit “our codes” frequently to help “demagnetize” (and re-adjust) our decision-making compass.

Please peruse the ethics category of this blog-site for other articles and sample references below.

PKF

Resources

- Website of Thomas W. Bailey, retired social studies teacher and attorney-at-law https://twbaileylaw.com/

- American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education webinar presentation Beyond the Obvious: The Intersection of Educator Dispositions, Ethics, and Law by Troy Hutchings and David P. Thompson https://smackslide.com/slide/ethical-equilibrium-aacte-2evrqb

- CT Teacher Education & Mentoring Program https://portal.ct.gov/SDE/TEAM/Teacher-Education-And-Mentoring-TEAM-Program

- Crossing Boundaries: Inappropriate Relationships https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zwQyoXy0kns and https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PL02yPaO81qEd7LWhJd1yPw0PPHVBMvyPx&v=kgI2OZdzO6Q

- Educator Ethics & Conduct Toolkit by Oliver Dreon, Sandi Sheppeard, PA State System of Higher Education, Professional Standards & Practices Commission: http://www.pspc.education.pa.gov/Promoting-Ethical-Practices-Resources/Ethics-Toolkit/Pages/default.aspx

- The Good Teacher: A Story of Sexual Misconduct www.leadershipcredit.info/docBase/The%20Good%20Teacher%20Storyboard5.pptx

- Education Week/Education Testing Service webinar presentation Professional Ethics – It’s Rarely About Right or Wrong by Troy Hutchings https://secure.edweek.org/media/190402presentation.pdf

- ETS Protecting the Profession – Professional Ethics in the Classroom by Troy Hutchings https://www.ets.org/s/proethica/pdf/real-clear-articles.pdf

- Iowa Board of Educational Examiners http://www.sai-iowa.org/Educator Ethics ppt NEW 2017.pptx and Ethics Facilitator’s Guide http://www.sai-iowa.org/Educator%20Ethics%20Facilitator%20Handbook%202017.pdf

- Lien, Joelle L. (2012). Ethical Dilemmas of In-Service Music Educators. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education. Online: http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Lien11_1.pdf

- Model Code of Ethics for Educators http://www.nasdtec.net/?page=MCEE_Doc

- NASDTEC An Introduction to Free and Currently Available Resources https://www.nasdtec.net/resource/collection/7C8FAAA3-65CF-4B6E-B0B4-801DDA91A35F/Free_and_Available_Resources___rev._Oct_2019_.pdf

- Nebraska Professional Practices Commission: https://nppc.nebraska.gov/

- Teachers’ Ethical Dilemmas – What Would You Do? https://www.redorbit.com/news/education/1141680/teachers_ethical_dilemmas_what_would_you_do/

PIXABAY.COM GRAPHICS:

- Doubt by Tumisu

- Teacher by 14995841

- Ethics by Olivier Le Moal (iStock-620005846)

- School Teaching by 14995841

- Teaching by 14995841

- Students by cherylt23

- High Five by skynesher (iStock-1224311229)

- Meeting by 14995841

- Business Meeting by jmexclusives

- Handcuffs by lechenie-narkomanii

- Homeschooling by vgajlc (iStock-1215474889)

© 2021 Paul K. Fox